User Guide#

For the following examples, we’ll use a dataset from an ecommerce provider to analyze their customers’ repeat purchases. The examples below are using the cdnow_customers.csv located in the datasets/ directory.

from btyd.datasets import load_cdnow_summary

data = load_cdnow_summary(index_col=[0])

print(data.head())

"""

frequency recency T

ID

1 2 30.43 38.86

2 1 1.71 38.86

3 0 0.00 38.86

4 0 0.00 38.86

5 0 0.00 38.86

"""

RFM Data Format#

All models require datasets in RFM (Recency, Frequency, Monetary Value) format:

frequencyrepresents the number of repeat purchases the customer has made, or one less than the total number of purchases. Repeat purchases made within the same time period are only counted as one purchase.recencyrepresents the age of the customer when they made their most recent purchases. This is equal to the duration between a customer’s first purchase and their latest purchase. (Thus if they have made only 1 purchase, the recency is 0.)monetary_valuerepresents the average value of a given customer’s repeat purchases. Customers who have only made a single purchase have monetary values of zero.Trepresents the age of the customer in whatever time units chosen (weekly, in the above dataset). This is equal to the duration between a customer’s first purchase and the end of the period under study.

For models using covariates, additional columns may be added.

Basic Frequency/Recency analysis using the BG/NBD model#

We’ll use the BG/NBD model first. There are other models which we will explore in these docs, but this is the simplest to start with.

from btyd import BetaGeoModel

# Similar API to scikit-learn.

bgm = BetaGeoModel().fit(data)

print(bgm)

"""

<btyd.BetaGeoModel: Parameters {'alpha': 4.5, 'r': 0.2, 'a': 0.8, 'b': 2.4} estimated with 2357 customers.>

"""

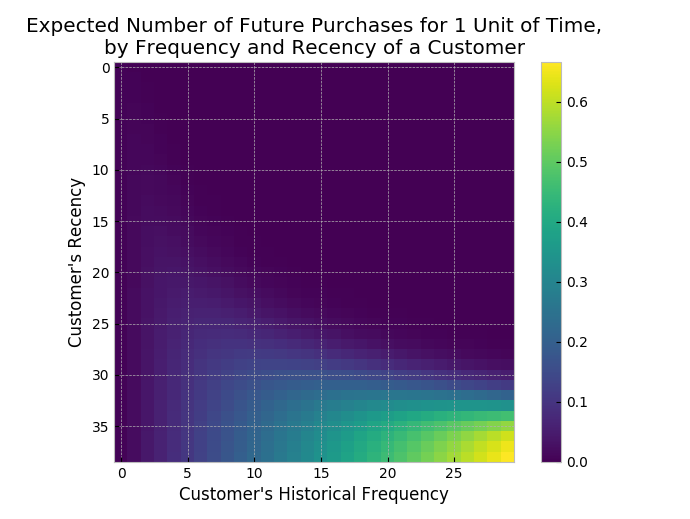

Visualizing the Frequency/Recency Matrix#

Consider a customer who bought from you every day for three weeks straight, and we haven’t heard from them in months. What are the chances they are still “alive”? Pretty small. On the other hand, a customer who historically buys from you once a quarter, and bought last quarter, is likely still alive. We can visualize this relationship using the Frequency/Recency matrix, which computes the expected number of transactions an artificial customer is to make in the next time period, given his or her recency (age at last purchase) and frequency (the number of repeat transactions he or she has made).

from btyd.plotting import plot_frequency_recency_matrix

plot_frequency_recency_matrix(bgm)

We can see that if a customer has bought 25 times from you, and their latest purchase was when they were 35 weeks old (given the individual is 35 weeks old), then they are your best customer (bottom-right). Your coldest customers are those that are in the top-right corner: they bought a lot quickly, and we haven’t seen them in weeks.

There’s also that beautiful “tail” around (5,25). That represents the customer who buys infrequently, but we’ve seen him or her recently, so they might buy again - we’re not sure if they are dead or just between purchases.

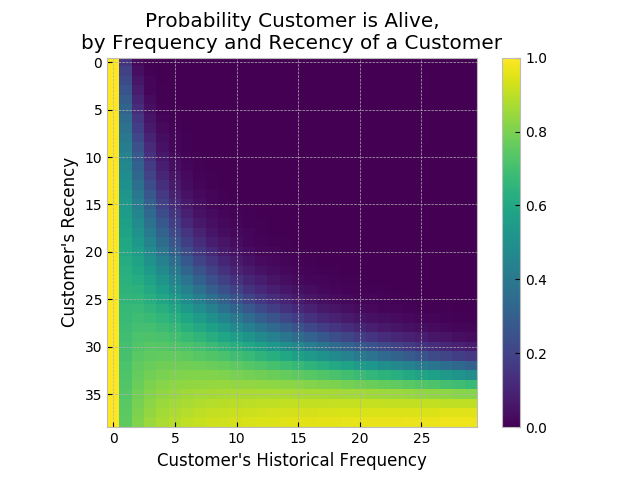

Another interesting matrix to look at is the probability of still being alive:

from btyd.plotting import plot_probability_alive_matrix

plot_probability_alive_matrix(bgm)

Ranking customers from best to worst#

Let’s return to our customers and rank them from “highest expected purchases in the next period” to lowest. Models expose a method that will predict a customer’s expected purchases in the next period using their history.

t = 1

data['predicted_purchases'] = bgm.conditional_expected_number_of_purchases_up_to_time(t)

data.sort_values(by='predicted_purchases').tail(5)

"""

frequency recency T predicted_purchases

ID

509 18 35.14 35.86 0.424877

841 19 34.00 34.14 0.474738

1981 17 28.43 28.86 0.486526

157 29 37.71 38.00 0.662396

1516 26 30.86 31.00 0.710623

"""

Great! We can see that the customer who has made 26 purchases, and bought very recently from us, is probably going to buy again in the next period.

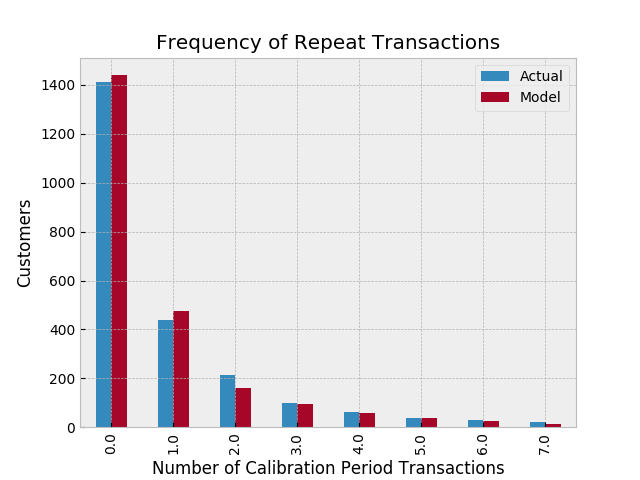

Assessing Model Fit#

Ok, we can predict and we can visualize our customers’ behaviour, but is our model correct? There are a few ways to assess the model’s correctness. The first is to compare your data versus artificial data simulated with your fitted model’s parameters.

from btyd.plotting import plot_period_transactions

plot_period_transactions(bgm)

We can see that our actual data and our simulated data line up well.

Example Using Transactional Datasets#

Most often, the dataset you have at hand will be at the transaction level. btyd has some utility functions to transform that transactional data (one row per purchase) into summary data (a frequency, recency and age dataset).

from btyd.datasets import load_transaction_data

from btyd.utils import summary_data_from_transaction_data

transaction_data = load_transaction_data()

print(transaction_data.head())

"""

date id

0 2014-03-08 00:00:00 0

1 2014-05-21 00:00:00 1

2 2014-03-14 00:00:00 2

3 2014-04-09 00:00:00 2

4 2014-05-21 00:00:00 2

"""

summary = summary_data_from_transaction_data(transaction_data, 'id', 'date', observation_period_end='2014-12-31')

print(summary.head())

"""

frequency recency T

id

0 0.0 0.0 298.0

1 0.0 0.0 224.0

2 6.0 142.0 292.0

3 0.0 0.0 147.0

4 2.0 9.0 183.0

"""

bgm.fit(summary)

# <btyd.BetaGeoModel: Parameters {'alpha': 1.86, 'r': 0., 'a': 1.85, 'b': 3.18} estimated with 5000 customers.>

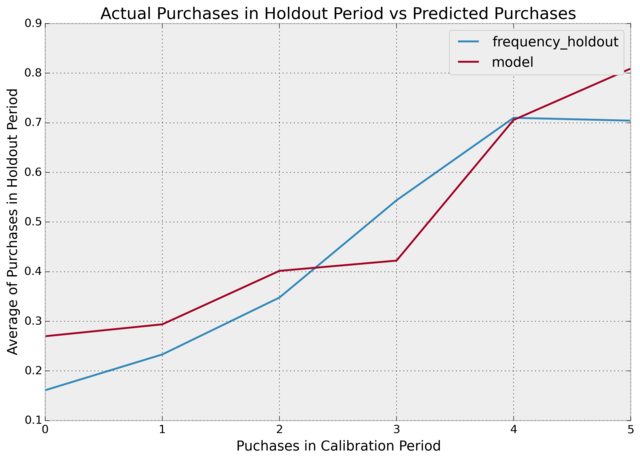

More Model Estimation#

With transactional data, we can partition the dataset into a calibration period dataset and a holdout dataset. This is important as we want to test how our model performs on data not yet seen (think cross-validation in standard machine learning literature). btyd has a function to partition our dataset like this:

from btyd.utils import calibration_and_holdout_data

summary_cal_holdout = calibration_and_holdout_data(transaction_data, 'id', 'date',

calibration_period_end='2014-09-01',

observation_period_end='2014-12-31' )

print(summary_cal_holdout.head())

"""

frequency_cal recency_cal T_cal frequency_holdout duration_holdout

id

0 0.0 0.0 177.0 0.0 121

1 0.0 0.0 103.0 0.0 121

2 6.0 142.0 171.0 0.0 121

3 0.0 0.0 26.0 0.0 121

4 2.0 9.0 62.0 0.0 121

"""

With this dataset, we can perform model estimation on the _cal columns, and test on the _holdout columns:

from btyd.plotting import plot_calibration_purchases_vs_holdout_purchases

bgm.fit(summary_cal_holdout)

plot_calibration_purchases_vs_holdout_purchases(bgf, summary_cal_holdout)

Customer Predictions#

Based on customer history, we can predict what an individual’s future purchases might look like:

t = 10 #predict purchases in 10 periods

individual = summary.iloc[20]

# The below function is an alias to `bfm.conditional_expected_number_of_purchases_up_to_time`

bgm.predict('cond_n_prchs_to_t', t, rfm_df = individual)

# 0.0576511

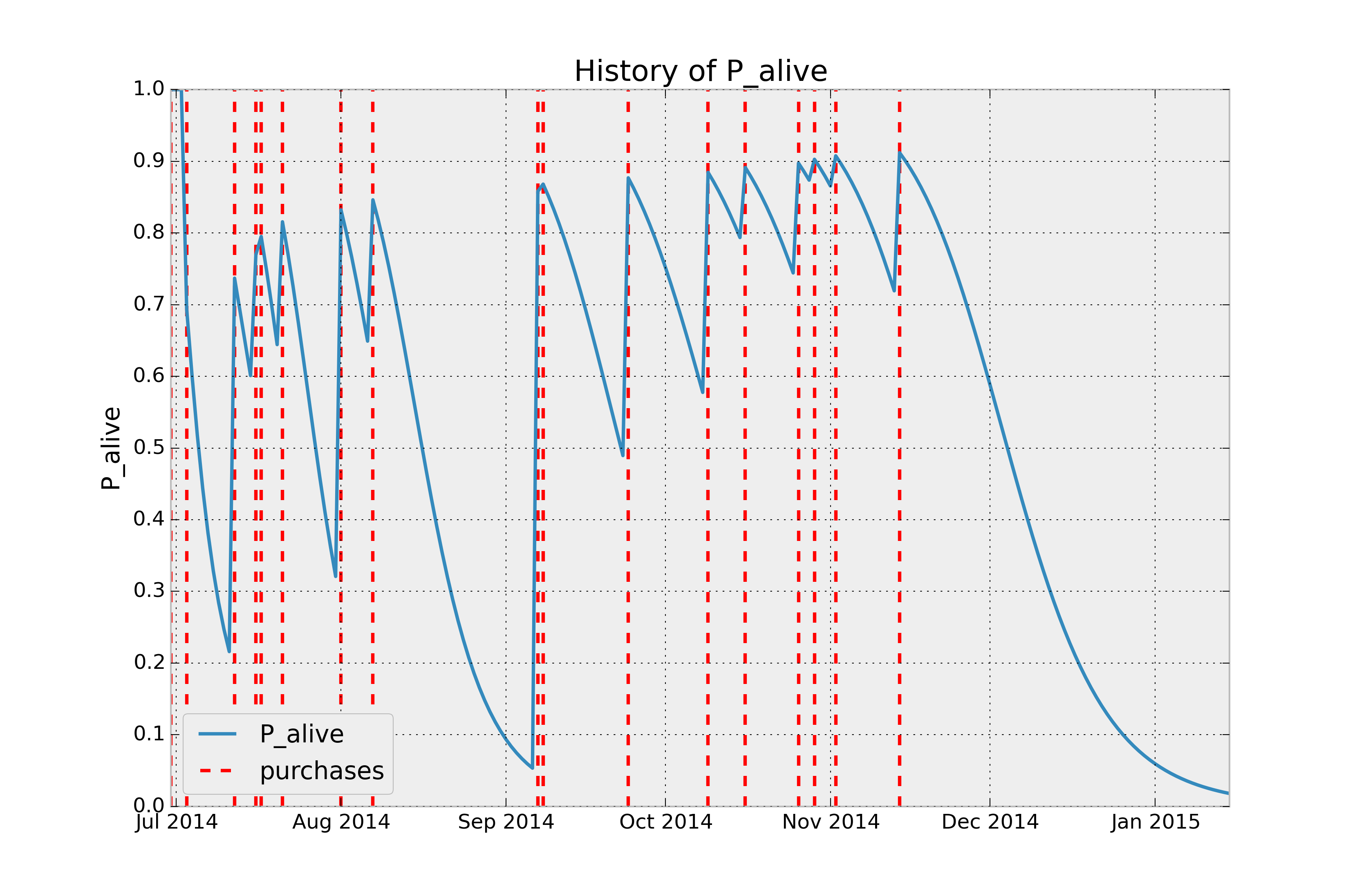

Customer Probability Histories#

Given a customer’s transaction history, we can calculate their historical probability of being alive according to our trained model:

from btyd.plotting import plot_history_alive

id = 35

days_since_birth = 200

sp_trans = transaction_data.loc[transaction_data['id'] == id]

plot_history_alive(bgm, days_since_birth, sp_trans, 'date')

Estimating Customer Lifetime Value using the Gamma-Gamma model#

Until now we’ve focused mainly on transaction frequencies and probabilities, but to estimate economic value we can use the Gamma-Gamma model. First we create summary data from transactional data also containing economic values for each transaction (i.e. profits or revenues).

from btyd.datasets import load_cdnow_summary_data_with_monetary_value

summary_with_money_value = load_cdnow_summary_data_with_monetary_value()

summary_with_money_value.head()

returning_customers_summary = summary_with_money_value[summary_with_money_value['frequency']>0]

print(returning_customers_summary.head())

"""

frequency recency T monetary_value

customer_id

1 2 30.43 38.86 22.35

2 1 1.71 38.86 11.77

6 7 29.43 38.86 73.74

7 1 5.00 38.86 11.77

9 2 35.71 38.86 25.55

"""

If computing the monetary value from your own data, note that it is the mean of a given customer’s value, not the sum.

monetary_value can be used to represent profit, or revenue, or any value as long as it is consistently calculated for each customer.

The Gamma-Gamma Model and the Independence Assumption#

The Gamma-Gamma submodel relies upon the important assumption there is no relationship between the monetary value and the purchase frequency. In practice we need to check whether the Pearson correlation between the two vectors is less than 0.3 in order to use this model:

returning_customers_summary[['monetary_value', 'frequency']].corr()

"""

monetary_value frequency

monetary_value 1.000000 0.113884

frequency 0.113884 1.000000

"""

Transaction frequencies and monetary values are uncorrelated; we can now train our Gamma-Gamma submodel and predict the conditional, expected average lifetime values of our customers:

from btyd import GammaGammaModel

ggm = GammaGammaModel()

ggm.fit(returning_customers_summary)

print(ggm)

"""

<btyd.GammaGammaModel: Parameters {'p': 6.25, 'q': 3.74, 'v': 15.45} estimated with 946 customers.>

"""

We can now estimate the average transaction value:

print(ggm.predict('cond_avg_profit').head(10))

"""

customer_id

1 24.658619

2 18.911489

3 35.170981

4 35.170981

5 35.170981

6 71.462843

7 18.911489

8 35.170981

9 27.282408

10 35.170981

dtype: float64

"""

print("Expected conditional average profit: %s, Average profit: %s" % (

ggm.predict('cond_avg_profit').mean(),

summary_with_money_value[summary_with_money_value['frequency']>0]['monetary_value'].mean()

))

"""

Expected conditional average profit: 35.2529588256, Average profit: 35.078551797

"""

And also compute the total Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) via the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discounted_cash_flow) while adjusting for cost of capital:

# Refit the BG model to the summary_with_money_value dataset

bgm.fit(summary_with_money_value)

print(ggm.predict('clv',

bgm, # the model used to predict the number of future transactions

time=12, # time periods (in this case, months)

discount_rate=0.01 # monthly discount rate ~ 12.7% annually

).head(10))

"""

customer_id

1 140.096211

2 18.943467

3 38.180574

4 38.180574

5 38.180574

6 1003.868107

7 28.109683

8 38.180574

9 167.418216

10 38.180574

Name: clv, dtype: float64

"""